The Search for Eden

There is a bizarre unease when you’ve done something you know is both absolutely right and wholly irrational, a sense that while you may forget the act, you will never forget the meta-act, your choice to damn all sensibility and indulge. This is a short story about how I bought E.V.O.: Search for Eden, a SNES game from 20 years ago that I basically already owned, for $150. It’s probably a story everyone relates to.

Kind of.

This post was actually supposed to just be about restoring the absolutely shitty cart I bought, obsessing even further about this ridiculous lark of mine, but in the end it came to be about why this apparently made sense.

In 1990, a Japanese game developer by the name of Almanic Corporation (eventually Givro Corporation, now nonexistent) released 46 Okunen Monogatari ~The Shinka Ron~ (literally, “4.6 Billion Year Story: The Theory of Evolution”), a game I never played for a system I never owned. Two years later Enix published Almanic’s follow-up, 46 Okunen Monogatari: Harukanaru Eden e (“4.6 Billion Year Story: To Distant Eden”), for the Super Famicom, the game eventually reaching the West as E.V.O.: Search for Eden. It’s a silly game, a fantastical mix of evolution and biology, platforming and RPG. You play as one life-form, traveling through the ages under the guidance of Gaia, evolving from a fish to potential bird or mammal combinations, along the way making decisions like “I need a better horn, so I’m going grind for a bit and eat these baby lizards until I get enough Evolution Points to buy a better horn. And then maybe I’ll grow a longer neck and get some sweet-ass wings.” In the end, you prove your genetic worth and herald a new age for the planet, and also become Gaia’s mate or something? It’s a bit strange.

It’s a pretty good game, and certainly distinctive, a shining example of the weird, magnificent stuff we got during the SNES era.

Anyway, E.V.O. is a game my mom must have rented for me a dozen times, my young self never good or dedicated enough to beat it, but always enamored enough to marvel at all the combinations of bodies and jaws and fins and horns and legs and so on that I wanted to play through it again. The game is a bizarre, near-surreal experience that even as a kid I appreciated like all novel and inexplicable things I’d managed to find. I imagine I begged her to buy it for me, and if the present day is any indication, she probably tried and couldn’t find it. If I knew then what I know now, I probably would have demanded we find it one way or another.

You see, I didn’t want to pay $150 for a SNES game — just the cartridge, specifically — that was pretty good but not exactly the shining paragon of its era. I had to. The game, bizarre and niche, had a smaller run, and is the kind of game idiot collectors (like myself) hang on to once they own it, the conversation piece they drag out when talking about video game madness, the thick, gooey nectar of nostalgia that one plays at least once a year, reminiscing on a childhood lost.

This is of course not unusual. I imagine most veterans of Media have their tangible items — fancy movie editions, first edition books of the classics, voluminous art collections or movie posters or vinyl records or whatever. Other games commonly exist in this realm too — Earthbound, for example, is another game I’ve lost and will one day own again. “This, The Legend of Zelda, is the first Nintendo game I ever owned, and it changed my life,” and so on.

Reclaiming these symbols, these trophies, is hard to justify. What have I bought, really, other than an antiquated plastic and silicon delivery mechanism for a couple megabytes of data? It’s ridiculous, honestly, an element of ridicule, to think of everything I could spend time acquiring — physical or mental or spiritual — instead of silly games about out-evolving a shark.

Memory is a strange thing. I believe heavily in subjective interpretations of the world, and following from that is an admission that one’s recollection (or lack thereof) changes their truth. There are beautiful, magnificent memories I have surely forgotten, people lost to my mind, experiences never recallable but that can never be truly novel, either. Is there much else to identity than this stuff, being able to conjure up again one’s roots? This, honestly, is the kind of stuff that keeps me up at night, wondering if ephemeral memory changes me when it escapes.

I guess this isn’t really foreign to anyone. This is why we photograph, we journal, we film. Why we keep trinkets around.

That brings us back to 46 Okunen Monogatari: Harukanaru Eden e. This quest of mine has been chewing at my mind for over a year, and last year I caved to my base nostalgia and game collecting craves, and bought the Japanese version of E.V.O., the otherwise identical 46 Okunen Monogatari: Harukanaru Eden e. I wanted to play the game on a real SNES again, with real hardware and a real controller in my hand, so I picked up this foreign facsimile of what I wanted to recall. I played it, said “yes, this is definitely the game I played with different language,” conquered the gameplay for the first time (in Japanese!) and then put it away. It wasn’t the same. E.V.O. represented something for me beyond a game, lacking it still felt like a hole, something I could only rely on my unreliable memory to keep as part of my identity.

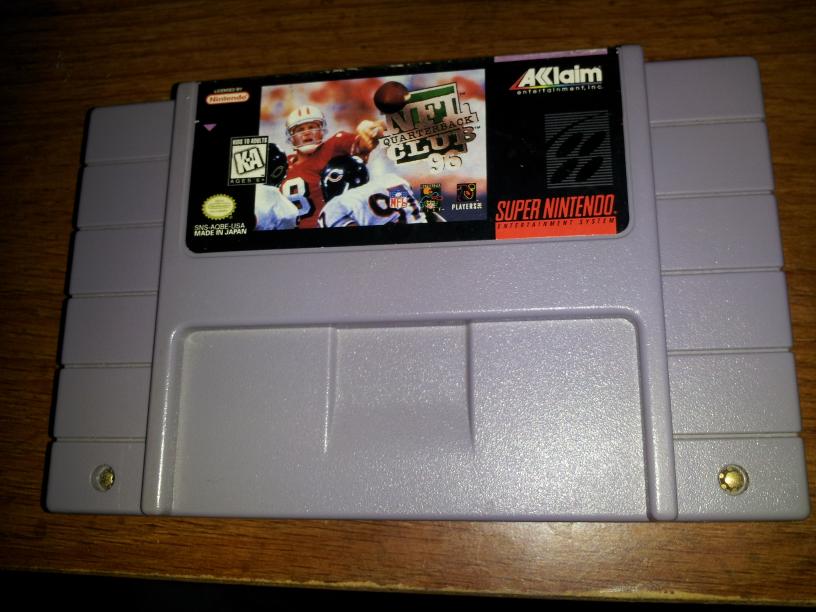

And that’s the story of how I spent multiple new games’ worth of money on a stickered-up, etched-into, grody-as-hell 21+ year old game, a couple lunches more on a replacement label, junk games to use as replacement shells, and security screw tools to crack this bounty open. The story of spending an hour scraping a NFL Quarterback Club ‘96 label off a donor cart and gouging gunk out of the gross E.V.O. shell’s screw holes just to have a nice cartridge to look at.

The story of rejecting the ephemeral.

This originally appeared on my old site, published on 2014-08-28.